Writing This Book Felt Like Spilling My Guts, But There Were Some Guts I Didn’t Spill

Multi-genre writer Amy Berkowitz reflects on three things she regrets leaving out of her first book, Tender Points, a decade ago

cw: childhood sexual abuse, ableism

The only time I’ve taken Ativan for something other than insomnia was a Friday evening in the fall of 2013. I was heading to an art gallery in North Beach to read from a work in progress that would eventually grow into my first book, Tender Points. I was going to stand in front of a room of people and say what happened to me, say it into a microphone: that I was raped by my pediatrician, that I repressed the memory, and that the morning after I recalled it as an adult, I woke up with fibromyalgia: chronic pain that never went away.

I was so scared of what I was about to do that I called a cab, an extravagance I rarely allowed myself at the time. The sweet, grainy tablet dissolved under my tongue as we moved through the night, my stapled pages tucked in my bag.

And then I got there, and I did it. I read from the work in progress, and I also read from Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, because the reading was part of Evan Karp and Lapo Guzzini’s Under the Influence series, where every reader shared the writing that influenced their own creation. And it was fine. The audience clapped, and then it was the next person’s turn to read. In fact, it felt good to say it out loud, what happened to me. To put it into words that people could understand. It made me feel less alone, now I wasn’t the only one alone with this memory.

The process of writing Tender Points and the book itself are both defined by their intimacy and vulnerability. I wrote significant portions of the book in bed — door closed, curtains drawn, warm glow from the nightstand lamp — because it was the only place I felt safe enough to let myself think about certain experiences. When I wrote something particularly disturbing, I hit the “return” key until the unsettling language vanished from the screen and I could forget about it until it came time to print out my collection of fragments and collage them into a book.

Tender Points was first published in the summer of 2015 by visionary, now-defunct indie press Timeless, Infinite Light (and later reissued by Nightboat Books in 20191). At the time, I couldn’t have imagined disclosing more about my experience. But looking back, I notice a handful of things are missing from the story.

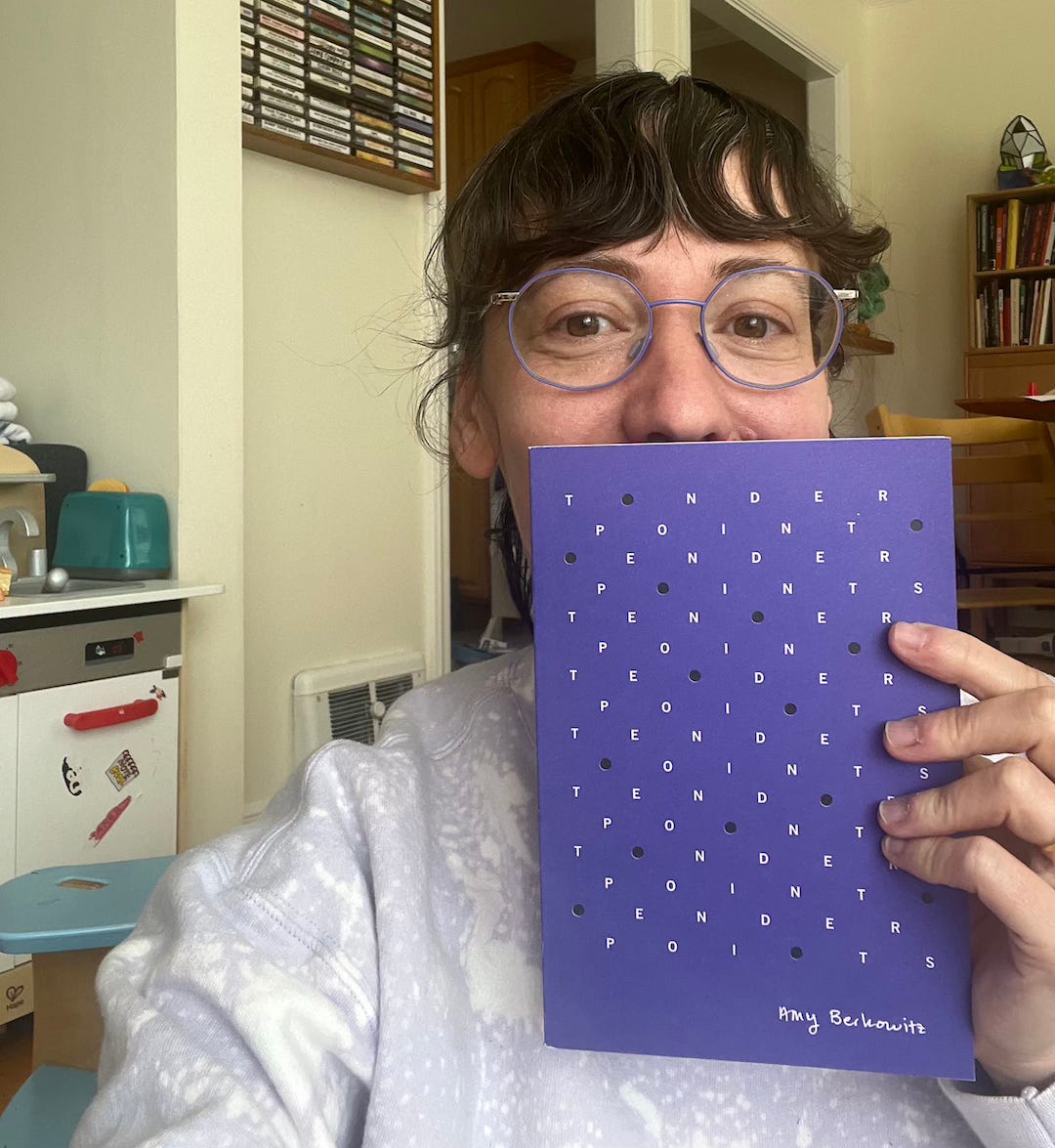

When I say regret leaving these parts of the story out, I don’t mean that I think the book is deficient without them. Tender Points is a book that recognizes the importance of absences and gaps — you can tell that just by looking at the cover (designed by Timeless, Infinite Light cofounder and generally very talented designer Joel Gregory), which is riddled with holes. The book’s title repeats eight times across the purple background, and each time there’s a hole punched through in place of a letter, so that the words are never intact.

Midway through the book, in describing a year’s worth of disappointing visits to vulvodynia specialists, I consider all the details I can’t remember:

The black holes in my memory become part of the story. I mean, they are the story.

When I talk about regret, what I mean is that I wish I could have felt safe enough, confident enough to say these things in 2015. I’m interested in writing about these lacunae because they give me a chance to reflect on how much I’ve changed and how much the world has changed in the decade since the book was published.

Here’s what I regret leaving out:

1. My queer identity

At the time I was writing Tender Points, I had kissed, dated, and yearned (oh, how I yearned) for women and nonbinary people, but I was hesitant to call myself queer, largely because I hadn’t found a queer community that accepted me.

Because I was bisexual, I was never considered queer enough, not even while I was dating my nonbinary partner, and certainly not after we broke up. As a result, Tender Points is a book about a woman and her boyfriends (the boyfriend who moves to Germany, the depressed noise musician boyfriend, the boyfriend she’s dating as she writes the book).

I was finally snapped out of this internalized biphobia during the Tender Points book tour I did in 2016. I had dinner with writer Tyler Vile after we read together in DC, and when I told her I didn’t call myself queer because I didn’t want to take up space, she corrected me, promised me that the only thing you have to do to be bisexual is be attracted to more than one gender.

That conversation inspired a scene in one of my current projects, Jumpsuits, a road novel about bisexuality, impostor syndrome, making and not making art, and the humiliating experience of becoming yourself. I remember the scene better than what Tyler actually said, so I’m including it here:

“You don’t want to take up space by identifying as queer?” Tor made a face, disgusted, like she’d taken a bite of something rotten. “Margo, that’s so stupid, where did you get that idea?”

Apparently the question was rhetorical, as Tor continued to rant, getting more and more incensed, body tense in her seat, one hand gripping the wheel and the other gesturing like she was giving a speech at a podium. “Take up space! As if there’s some finite amount of space, as if there can only be a certain number of queer people in the world and they all have to be queer in the right way. Jesus Christ!” Now the van was swerving a bit, struggling to stay in its lane. “Sexuality is about desire! If you want to fuck more than one gender, you’re bisexual. It’s not complicated.” Her words washed over me, quenching a very specific and desperate need. Everything I felt about my sexuality, everything I felt about the way Liana dismissed it, here was someone validating all of it, putting my anger into words, smart words that I could carry with me.

Including my bisexuality in Tender Points would have allowed me to write about the intimacy I’ve shared with women and nonbinary partners who had their own experiences with chronic pain and trauma. It also would have let me explore the parallels between bisexuality and invisible illness: the feeling that you’re not queer enough, not disabled enough. In both cases, you find yourself asking, do I belong here? Am I taking up too much space? But at the same time you're not able bodied, and you're not straight. You're not enough in either space. While being able to pass as able-bodied and straight certainly offers specific advantages, it feels weird and alienating to have both my disability and my queerness — two core, defining aspects of my identity — be totally invisible.

2. My other disability

As a woman, a survivor of sexual assault, a person with fibromyalgia, and someone who recalled a repressed memory of trauma, I already had four strikes against my reliability as a narrator. I felt that disclosing my bipolar disorder would take things a step too far, would make me so unreliable and unrelatable that readers wouldn’t believe or connect with my story at all.

Maybe it’s cynical, but I think I may have been right. At least in 2015.

I’m trying to remember if I did any writing about my experiences with bipolar in early drafts of Tender Points or if it was just something I thought about including. I searched my original Google doc for the word and found just one mention, in a quote pulled from a message board conversation where men were complaining about women who “pretend” to have what they called “fake o myalgia”:

Lotta them have depression, anxiety or bipolar disorders too. They have weird “allergies” too, Tylenol, NSAIDs, anti-psychotics... Nut jobs most of em.

In researching my book, I spent time lurking on message boards like this, studying the prevalent hatred and distrust of women with chronic pain. What I learned was that people already thought women with fibromyalgia were “nut jobs” simply because they had fibromyalgia. Even if I didn’t mention bipolar, it was going to be hard enough to get readers to listen and believe me. I was worried that if I revealed that I actually was a nut job, the fact of my mental illness would cast yet another layer of doubt on everything I wrote, a layer thick enough to totally blot out all that was underneath.

(I’m imagining a Goodreads review by a reader who put this imagined version of the book down before finishing it: She thinks her pain is related to being sexually abused in childhood and she says she only remembered the abuse twelve years after it happened? Is that even possible? Whatever, she’s bipolar, who knows. DNF.)

I can’t remember when I first learned about the link between trauma and bipolar disorder — was it while I was writing Tender Points or after? To summarize: it’s very common to have both PTSD and bipolar, PTSD increases your risk of developing bipolar, and oftentimes PTSD is misdiagnosed as bipolar.2 Even before I read these facts, I intuitively understood that my experience of bipolar disorder was linked to the traumatic event. The mood disorder was just another way I was experiencing the trapped memory of the trauma; it wasn’t just haunting my body, it was haunting my mind, too. Of course that belonged in the book, but I wasn’t ready to say it.

It feels important to point out that I started writing Tender Points a few months after finally accessing care for bipolar disorder (after being misdiagnosed and lacking support for many years). The resulting stability is what allowed me to feel safe enough to think and write about my memories of sexual abuse and retraumatizing doctor visits. That’s another reason why it would’ve felt meaningful to acknowledge the fact of my mental health in the book: because finally accessing treatment was the reason I was able to tell the story.

3. The event that made me remember the trauma

Recalling my childhood trauma is the fulcrum of my story, the moment that changed everything: one night, I went to bed an able-bodied person who had a vague sense that nothing especially terrible had ever happened to them, and then I recalled the traumatic memory and woke up with chronic pain that never went away. That’s what made me write Tender Points — the shock of becoming a chronically ill survivor of sexual assault overnight, and the desire to make sense of what happened to me.

I was so focused on the fact of the repressed memory and how it haunted my body that it didn’t think much about how I came to remember it, but that’s a central part of the story too.

Here’s how I imagine it could show up in some other alternate universe version of the book where I’d decided to include it:

∆

The shoulder pain was getting worse, so I visited a doctor a few blocks from my work. She had a sunken, garden-level office on St. Mark’s Place, such a strange place to visit a doctor. You went to St. Marks to get a tattoo, a fake ID, cheap sunglasses, late-night Japanese food, not medical care. Anyway there I was on this street in her basement office and she asked me to raise my arms. When I did, one of my shoulder blades stuck out more than the other one. I saw this in the mirror and I saw her laughing, too: she was standing behind me, laughing out loud at how asymmetrical my body was, at the problem I was trusting her to solve. After laughing at me, she sent me to a little room in back where a man used a massage gun on my muscles. The pain was terrible and I guess I must have been making some kind of noise in response to it because the doctor soon burst into the little back room and shouted at me to be quiet, I was scaring the other patients. I surprised myself by standing up and demanding that she leave the room, that this was my appointment and I was here to be treated for my pain, and she had no business talking to me that way. I paid my copay, thinking, I can’t believe I’m paying for this, and then left the office and started crying. I walked west, thinking I’d get the train home to Brooklyn, the station was only a short walk away, but by the time I reached the end of the block, I realized I couldn’t really handle crossing the street. I had plenty of experience crying but I had never cried like this, totally ensconced in a literal veil of tears that was both physically and psychically impossible to see through. I held out a hand and waited for a cab to find me. While I was waiting, a man gave me his business card: a therapist. I wondered if this was how he found all of his clients.

And it was that night, a few hours later, lying in bed, about to fall asleep, when I remembered something that had happened with a different doctor, when I was a kid, when I hadn’t been able to stand up for myself at all.

I don’t know if it really fits — the perspective I have today on both the childhood trauma and the bad doctor visit is so different from the perspective I had when I wrote the book. I truly feel like a different person now, and I don’t think it’s possible to just slip something into a book I wrote then, or at least not without writing it in the voice of some kind of persona, “2015 Amy.” Or maybe I’m wrong, maybe this would fit in seamlessly and I’m the only one who’d know the difference.

Reflecting on my memory of this unkind basement office doctor, recognizing it as an essential part of the story, I find myself wondering: what if I’d never seen her? What if I’d walked into that appointment and met a competent and caring practitioner who helped me find relief from my shoulder pain? Would I never have remembered the repressed memory? If I’d gone through life without encountering any disrespect from medical professionals (granted, not a likely scenario) maybe the memory would never have surfaced. But this is the moment that brought it to me, and I see it as an important part of the puzzle.

Another Tender Points

I never planned to write another book like Tender Points. Since its publication, I’ve written a book of poems (Gravitas, which came out in 2023) and two novels, one of which is excerpted here. I figured I’d said everything I needed to say about medical sexism and I was happy to be writing mostly fiction.

But then a couple of years ago, someone joked that I was going to have to write another Tender Points. It was my doula, and she was in my kitchen, cooking stew for us a few weeks after our kid was born. She didn’t normally offer postpartum support but she was helping us because my birth had left me more disabled than we’d expected. In addition to a C-section that prevented me from lifting things or sitting up by myself, I’d left the hospital with a nerve injury that made it hard to walk: I couldn’t feel my left ankle or foot, and I couldn’t flex my ankle, so I had to kind of drag my foot when I walked.

The doula told me that she wished she could warn her clients about nerve injuries from epidurals, but it was mostly all anecdotal, just one or two studies, and most of her clients only wanted an epidural in case of emergency anyway.

She told me she’d seen a lot of people get nerve injuries from anesthesia, and every time it happens, the anesthesiologist says the same thing: that it’s impossible.

I think that was the moment she joked that I’d have to write another book about medical sexism; her remark was in response to whatever face I made when she explained how anesthesiologists systemically erase the harm they cause. Of course there was a book there, but I had no desire to write it. I didn’t want to think about how bad my birth experience had been, I wanted to go back to writing the fun, queer road novel I’d started before I had the baby. But I couldn’t do that. I had postpartum depression, but I wouldn’t figure that out until the worst of it was over, at least six months in.

I started a document called Notes Towards Some Thing (unusual spelling of “something” due to dictating into my phone). I wrote about the nerve injury, what the doula said, feeling numb (physically), feeling numb (emotionally), feeling fundamentally changed, how strange pumping was, how alone I felt.

Four months postpartum, I realized the project had a name, and that I did want to write it, even though I resented the responsibility of having to. Monster Truck Rally would be a book about the link between postpartum depression and birth trauma, the surprising name a gesture towards addressing a drastically broader audience than the very limited one targeted by the pastel array of titles on these subjects. Sometimes it does feel like a sibling to Tender Points; my friend Elliott likes to call it 2 Tender 2 Points. The main formal difference is that I’m experimenting with titling each section. But the biggest difference is me: I’m simply a different person than the person who wrote Tender Points. Becoming a parent has made me trust my instincts more than ever before. It’s made me realize I’m nonbinary. It’s made me do almost all my writing by dictating into my phone, a practice I really can’t recommend enough.

From Monster Truck Rally:

Half Bear

My husband is next to me in bed, absorbed in his book, and I’m restless, scrolling. I ask what he’s reading and he tells me it’s a book by a woman who was mauled by a bear. And not only was she mauled by a bear, he adds, she happened to be an anthropologist who was familiar with a belief that if a person is mauled by a bear, they then become half bear.

Mauled by a bear is unarguably an experience remarkable enough to write a book about, which makes me suspect that this experience is not: Unlike being mauled by a bear, birth trauma and postpartum depression are anything but remarkable.

What traumatic birth does have in common with being mauled by a bear is fear, surviving (or not), and medical intervention that may do more harm than good. In this woman’s case, the doctor who treated her in Russia botched her jaw replacement, and the team who corrected it in Paris didn’t sanitize their instruments and gave her an infection.

So if being mauled by a bear leaves you half bear, surviving traumatic birth leaves you what? I attempt an inventory of what I am and it’s inconclusive, just a fuzzy awareness that I’m something different than what I was.

But maybe that’s every birth, you always become something different: You become a parent.

It’s impossible to know what I’ll regret leaving out of Monster Truck Rally ten years from now, because it’s impossible to know who I’ll be ten years from now. And when you think about it, that’s kind of thrilling.

Amy Berkowitz (she / they) is the author of Gravitas (Éditions du Noroît / Total Joy, 2023) and Tender Points (Nightboat Books, 2019). She lives in San Francisco, where she cohosts the Light Jacket Reading Series. They’re currently working on a novel and a nonfiction project.

Follow Amy on Instagram and Bluesky.

This isn’t my first time looking back at Tender Points. I wrote an afterward for the 2019 Nightboat Books edition about a seismic shift I’d experienced since starting the book in 2013: when I first started writing Tender Points, I didn’t identify as disabled. I had no idea that chronic illness “counted” as a disability or that connecting with other disabled people and disability culture would make me feel so joyful, validated, and proud. From the afterward:

“I was isolated from other chronically ill people and survivors of assault, so my pain and my assault felt like personal problems I needed to sort out. That’s why I started writing the book. What I didn’t know when I started writing — what I didn’t know I could even hope for — was that the process of researching, writing, and reading from Tender Points would eventually connect me to other sick people and survivors and introduce me to sick and disabled communities.”

https://www.healthline.com/health/bipolar-disorder/ptsd-bipolar

Yeah ableism does a number on us, especially if we have invisible disabilities. Super happy you’ve found sick & disabled communities.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about audience. Who am I writing for? I’m not sure I even want to write for able bodies people anymore. Your thoughts?